Reviews for His Brother's Keeper: A Story from the Edge of Medicine

His Brother's Keeper: A Story from the Edge of Medicine

New York: Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers. $26.95

See what the reviewers had to say about the book:

New York Times Book Review

Los Angeles Times

Philadelphia Inquirer

Publisher's Weekly

BOOKLIST

Austin American-Statesman (Texas)

Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio)

Entertainment Weekly

The Kansas City Star

Tampa Tribune (Florida)

Library Journal

Ottawa Citizen

Raleigh News and Observer

New England Journal of Medicine

Scientific American

Seattle Times

Washington Post

KUOW-FM (NPR, Seattle)

The New York Times Book Review, April 18, 2004

By Stephen S. Hall

Family Science Project

Among many exquisitely rendered moments in Jonathan Weiner's "His Brother's Keeper: A Story From the Edge of Medicine," a simple daily act of fine motor skill early on quietly explodes into a moment of heartbreaking significance, when a young carpenter named Stephen Heywood inserts a key one morning into the front door of a cottage he has been lovingly restoring in Palo Alto, Calif. A self-described slacker, a brown dwarf of a star in an otherwise brilliant constellation of familial ambition, Stephen has struggled to find his niche, professionally and perhaps emotionally, in a family of overachievers based in Newton, Mass. His mother, Peggy, is a retired psychotherapist; his father, John, is director of an engineering lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; his younger brother, Ben, is trying to make it in Hollywood as a producer; and his other brother, Jamie, two years older, is not just an M.I.T.-educated mechanical engineer of uncommon vision and intuition, but a larger-than-life personality who has yet to meet a challenge he cannot overcome. The family's greatest challenge begins to announce itself that morning in December 1997, when Stephen discovers that try as he might, he is unable to turn the key in the lock with his right hand. It is an early sign that he is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (A.L.S.), often called Lou Gehrig's disease.

The main story line of Weiner's gripping book follows the efforts of this remarkable family, and especially Jamie, as they race to find a cure for Stephen. But Weiner -- who won a Pulitzer Prize for his account of Darwinian evolution, "The Beak of the Finch," -- has a larger canvas in mind. He sees the Heywood saga as a cautionary tale about the promise and peril of contemporary biomedical research, when "the power of human understanding had reached a point at which it was possible to view all of life as a project in molecular engineering, and the saving of life as nothing more than engineering and genetic carpentry."

Hence, the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1997 forms a dark backdrop against which the more intimate narrative of the Heywood family unfolds in 1999 and 2000. The urgency of their quest is manifest. A.L.S. is an irreversible neurodegenerative disorder in which motor neurons in the spine slowly die off, one by one; in its particularly gruesome ending, the patient suffocates to death or chokes on his own saliva. The very first paper about A.L.S. that Jamie Heywood calls up on the Web reports that most patients die within two years of diagnosis.

Jamie, Weiner tells us, was known as "the Repair Man," because he could fix anything. He scours the Internet for clues. He cold-calls the top researchers in the field, neuroscientists like Jeffrey Rothstein at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and pioneering molecular biologists like Matthew During at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He sets up a foundation and later forms a biotech company with During; in fact, he eventually helps During run his lab meetings, and even tries to fire one of his postdocs. His wife, Melinda, a teacher of French literature who trained as a belly dancer, performs at local benefits to raise money.

As Jamie's grandiosity swells, everything becomes secondary to his quest to+cure not only A.L.S. but "one incurable disease after another." In one of Weiner's recurrent and understated motifs, we see Stephen tiptoeing in the background of all this well-intentioned hubbub. He slowly remodels his parents' bathroom (he's moved back home), begins a courtship with his eventual wife, Wendy, and quietly defends his independence and dignity.

In a phenomenal job of reporting, Weiner practically becomes a sixth member of the Heywood family. He stays at the home of the parents, goes to church with them, visits scientists with them. When Stephen receives his "death sentence" diagnosis from a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Weiner is able to recreate, from a tape of the conversation, every pained "um" and "uh" of the doctor's remarks; never has such a grim discussion seemed more awkwardly realistic on the page. In conveying the dysfunctional neural signaling that characterizes diseases like A.L.S., Weiner creates an extended metaphor, drawn from the Kafka short story "An Imperial Message," that is as fine as any I have read.

But there is a meta-question here. If Jamie's quest is plausible, then this story becomes a heroic effort worthy of our greatest respect. If he is in over his head, it becomes something of a fool's errand, with a different set of ramifications -- not only for the Heywoods, but also, to the extent that a rushed and ill-considered experimental treatment can set back an entire field for years, for all patients with neurodegenerative disease.

While wrestling with this question, Weiner becomes a character in his own narrative. First, we learn that his 74-year-old mother, known as Ponnie, suffers from a rare, progressive and incurable neurodegenerative disease of her own; suddenly, his observations are not entirely neutral (indeed, he's rudely introduced to the pay-as-you-go ethic of entrepreneurial biology when Matt During suggests that his lab can work on some animal experiments related to his mother's condition -- for $10,000). As he admits at one point, "I was falling out of the reporter's role." It also becomes clear -- perhaps sooner to the reader than to the author -- that Weiner has been seduced by Jamie and his crusade. "I thought that I had never seen anyone so young, gifted, ambitious and deserving of a fortune," he writes. "I would make his legend."

Thus the tension in the unfolding narrative stems not only from whether Jamie can save Stephen, but whether Weiner will experience the storyteller's version of buyer's remorse. There is a scientific component to his investment, too. Jamie's grand plan to save Stephen involves a technology called gene therapy. To Weiner, gene therapy, "more than any other field of medicine, had the aura of the future about it, the ring of impossible promise." But gene therapy is also one of those stories in modern biomedicine that has never progressed beyond sounding good to being true. Despite hundreds of clinical trials by some very creative scientists with thousands of patients, gene therapy has not had a single unambiguous success.

And this leads to what is, in my view, the most fascinating aspect of "His Brother's Keeper." As Peter Medawar, the British immunologist and Nobel laureate, shrewdly noted, scientific theories "begin, if you like, as stories, and the purpose of the critical or rectifying episode in scientific reasoning is precisely to find out whether or not these stories are about real life." About two-thirds of the way into the book, Weiner has what feels like a Medawar-like epiphany. He begins to wonder whether the story he has been chronicling is indeed a story about real life in the scientific sense. "In retrospect, I can see that the story already was jumbled in my head," he says. "I could no longer tell how much of our hope was real; and sometimes, when he was at his most electric and charismatic, I still wondered how much of Jamie was real."

Those of us who write regularly about medicine have all been there; what makes the craft particularly difficult is discerning when a story is real or not in Medawar's sense, even as -- especially as -- it is unfolding. But this is an extraordinary confession, and Weiner heard plenty of warnings along the way. Arnold Levine, then president of Rockefeller University, told him he despised "the hype and flimflam around gene therapy and regenerative medicine." Weiner seasons his account with many caveats, but the narrative is so dominated by Jamie's soaring -- and, as it turns out, misplaced -- confidence that they barely register. This might qualify as a flaw, but actually it enriches the book, because a riveting feature is Weiner's gradual, grudging and admirably candid realization that he has perhaps bought into a story of hope that may not be real. By February 2000, when his long account of the Heywoods in The New Yorker comes out, the author has begun to distance himself -- not so much in the article, but in the book, where he describes Jamie driving all over Boston, snapping up more than 300 copies of the magazine. The heroic quest begins to feel like an ego trip.

The most disturbing aspect of this otherwise very engaging book is that when Weiner crashes from his Jamie infatuation, he lands smack on the entire biomedical research enterprise. Although it feels like a reach, he places the Heywood story within the larger hubristic orbit of modern biomedical ambition, including human cloning; a tone of elegant alarm colors his view of the research paladins who, in attempting to do good, threaten to "change human nature." Precisely because he is such an astute and thoughtful observer of the scientific scene, I found these sentiments surprising. Several well-known -- if not universally admired -- scientists get squashed by Weiner's crash landing. Jacques Cohen, the flamboyant I.V.F. specialist at the Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Science of St. Barnabas in Livingston, N.J., coyly hints a willingness to clone a human child -- for $10 million. Lee Silver, a molecular biologist at Princeton who has increasingly become a cheerleader for human reproductive cloning, is described keeping a meticulous album full of his press clippings.

Therein, I think, lies a crucial distinction. With some of the scientists in the book, and especially with Jamie, it is easy to confuse hype with science, publicity hounds with serious researchers, presumptive stories with a "real" story. It's hard to argue that Jamie embodies the can-do arrogance and unbridled power of modern biology when he is described, deep into the book, as being in way over his head. Yet we -- not just the chroniclers of these stories, but the consumers of them -- are part of the problem, because we much prefer the uplifting mythology of "brilliant" mavericks and "curing the uncurable" to medical stories with headlines like "Small Step Forward Achieved; Much Work Remains to Be Done." Perhaps the most valuable message of "His Brother's Keeper" is that hope is a precious resource, and like any precious thing it should not be invested without due diligence.

I don't entirely agree with Weiner's implication that "the edge of medicine" is overrun with cowboys and rogues, though they surely share space there with serious researchers. The larger point is that it's become harder and harder to distinguish the two, which is why I think Weiner's analysis is enormously valuable. Entrepreneurial biology has been inviting this kind of eloquent, non-ideological backlash for years, not simply in the literal sense of commercializing discoveries in the private sector (often at great personal financial reward), but in the figurative and cultural sense of its relentless salesmanship. As a lowly postdoctoral fellow tells Weiner: "Science takes time. Jamie wanted us to give him something he could put into his brother tomorrow. And he felt like anything short of that was just -- being lazy, or that we just simply didn't understand. And I think it was just the other way around. Jamie just didn't understand how science worked."

In the fall of 1999, after an 18-year-old volunteer named Jesse Gelsinger died in a clinical trial at the University of Pennsylvania, a huge cloud gathered over the field of gene therapy. Jamie Heywood and Matt During had to abandon their plans to attempt it for Stephen. Instead, in May 2000, he received an experimental stem cell treatment -- a treatment that Rothstein, the Hopkins neurologist, dismissed as "just ludicrous. I'm appalled." By the end of "His Brother's Keeper," we learn, inevitably, that the treatment didn't work. Jamie's wife has left him, and he rarely brings himself to visit Stephen. Weiner's own "family disaster," meanwhile, has seen his mother contract into a shell of her former vibrant self, and he professes disgust with the edge of medicine. But he also gives us a final satisfying glimpse of Stephen, in a motorized wheelchair in the restored carriage house, communicating to his young son, Alex, through a computer, happy with what he has rather than disappointed at what Jamie, and science, could not give him. It is a beautifully told tale, marred only by the intimation that we should not keep trying to rewrite its ending.

back to top

Los Angeles Times, March 21, 2004

By Mark Dowie

The human face of gene therapy

Science is a difficult thing to communicate to nonscientists, now more than ever with familiar sciences such as biology, physics, chemistry and cybernetics morphing into new sciences, some of which exist beneath our line of sight, where the laws of nature hover between Newtonian and quantum mechanics.

Few scientists know how to make this world real to each other, let alone to the rest of us, and those who do are often reviled by their peers for popularizing something best left in the laboratory. Thus we laymen must rely on articulate mass media science writers to keep us abreast of subjects we left behind in our sophomore years. They master the language and complexity of new fields such as cyber-, bio- and nanotechnology and carry us with ease through the most arcane and baffling concepts. We are intrigued and empowered by their gift.

Jonathan Weiner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer-in-residence at Rockefeller University and former editor of the Sciences magazine, has been justly awarded for previous books about matters as diverse as the love life of fruit flies, the ever-evolving beaks of Galapagos finches and the future of the planet we occupy. Now he turns to medicine and recounts a desperate personal quest to cure an intractable orphan disease with untried, highly controversial gene treatments. The result is a captivating, suspenseful narrative, full of complex, fascinating characters and loads of pathos.

"His Brother's Keeper: A Story From the Edge of Medicine" is a science drama involving the illness of one member of an amazing family. When Stephen Heywood, the second of three brothers, is diagnosed at 29 with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig's disease, his older brother Jamie transforms himself overnight from a mechanical engineer to a genetic engineer in a desperate quest to save him.

ALS is a devastating, incurable neurological disorder that rapidly destroys the motor nerves of its victims. Their lives end in unimaginable agony and suffocation, generally, about two years after diagnosis. This is not something Jamie Heywood ever wants to watch.

As the story unfolds and Stephen's condition worsens, Jamie is variously motivated by rage, ambition, curiosity, fame and profit to find a way to regenerate lost neurons somewhere in the fast-growing but still infant field of genetic medicine. But above all he is driven, at times into caffeinated frenzy, by a compulsive resolve to save his brother's life.

When Stephen is diagnosed, Jamie leaves a lucrative career in La Jolla, Calif., and moves home to Boston where his brothers and their parents still live. Weiner follows him to become all but a member of the family. And what a family -- tight-knit, loving and defiantly loyal. Anyone would want to be part of it, most of all a solitary writer accustomed to lonely nights in motels, long rides in rented cars and impersonal interviews in neutral locations.

I envied Weiner being with the Heywoods, although as a fellow reporter I began to wonder how objective or dispassionate anyone could be when he stays overnight in their houses, parties at their cottage, joins them at church and drives thousands of miles up and down the East Coast with them, from Boston to New York to Baltimore, as they raise money and beseech molecular biologists, geneticists and clinical physicians to join their private war against ALS. Weiner admits, "I was hooked." And I realized I would have been too.

The plot thickens when Weiner's mother is diagnosed with a rare neurological disorder called Lewy Body dementia. I can imagine his editor asking whether the author and his mother needed to be injected into the drama that was engulfing the Heywood family.

But it turns out that Lewy Body is a condition that could be cured by some of the same treatments being considered for Stephen. So this additional drama works, and we join the Weiner family as Jon Weiner joins the Heywoods.

In the course of his research into the science behind the treatments, Weiner signs a can't-write-about-it-for-three-years contract and joins another desperate voyage. A Caribbean cruise ship called the Galaxy sets sail from Miami. On board is a small group of geneticists and fertilization specialists who are dodging the glare of media, the judgment of bioethicists and the intrusion of government for a week at sea.

In safe international waters they discuss some of the more controversial and ethically challenged procedures emerging in their practice. The most riveting debate is over germ line engineering, which offers the ability to permanently alter the human genome in such a way as to breed a superhuman species that cannot interbreed with its genetically inferior ancestors.

Weiner witnesses an exchange any journalist would die for. And he returns to shore wondering whether this genetic manipulation is responsible medicine.

That sort of question, alongside the growing doubts among bioethicists about experimental procedures on consenting terminal patients, sends Jamie Heywood into a rage. "That's just like totalitarianism," he tells another reporter. "If we've gotten to the point where human beings aren't capable of making decisions in their own best interests, then what kind of society do we believe in?" But this is not a simple decision, Jamie is soon to discover, for either Stephen or the dozens of scientists and physicians Jamie has recruited to his cause.

There are two interventions possible for Stephen. One injects healthy stem cells either into his spinal column or directly into his brain. The other infinitely more experimental and complex procedure involves a neurological vaccine made by inserting DNA into billions of viruses and injecting them into the patient in the hope that they will penetrate nerve cell walls, find their way to the nucleus and instruct it to produce a chemical that will block the cellular production of glutamate, an amino acid that in excess kills nerve cells -- the mechanism of ALS.

Stem cells had been tried on a few ALS patients in their endgame. Results were not encouraging. The vaccine was untried. Which was right for Stephen, the stem cells or the neurovaccine? Or was either treatment right for anyone?

Perplexed by that question, Weiner calls Arthur Caplan, the most widely quoted bioethicist in the country, a man whom I have known to answer his phone on the first ring. When he hears the question, Caplan does not hesitate to express an opinion looming in his practice about stem cells and gene therapy.

"My skepticism about all this is somewhere between unbounded and enormous," he tells Weiner. Stem cell therapies, Caplan says, belong "on a five year plan, not a short term plan," and adds, "the fact is you can be made more miserable -- even though it doesn't seem possible -- by interventions."

And therein lies the central question of this story and of regenerative medicine itself. How far can we go in experimentation, even with dying patients still competent to provide informed consent? The value of books like "His Brother's Keeper" is that they force the healthy to address such questions while they are healthy, rather than waiting until they and their frantic family are driven by desperation to find a silver bullet. At that point they are at the mercy of medical cowboys like the geneticists on board the Galaxy who discussed practices and procedures they did not want us to know about until they had mastered them.

It's not the first time this has happened in medicine. Nor will it be the last until we, the consumers of treatment, better understand what they are talking about. For that we can be grateful to writers like Jonathan Weiner.

back to top

Philadelphia Inquirer, March 28, 2004

By Bruce E. Beans

The book began with a familiar source.

From the Galapagos Islands to fruit-fly laboratories, celebrated Doylestown science writer Jonathan Weiner has gone far to understand our world and how and why we are in it. But no journalistic journey he has undertaken has proven as emotionally wrenching or personally compelling as that for his new book, His Brother's Keeper: A Story From the Edge of Medicine.

"Have I got a story for you!" Ralph Greenspan, a senior fellow at the prestigious Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, Calif., told Weiner over the phone five years ago.

Since a tip from Greenspan had led to the book Weiner was then about to publish, the writer was primed to hear more. Greenspan talked about a young engineer at the institute, Jamie Heywood, whose younger brother Stephen had just been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease. When hearing that a loved one has an incurable illness, some people might pray. Some would donate organs. Others might relentlessly pursue the best doctors and the most advanced, even experimental, treatments.

Not Jamie Heywood. The 32-year-old Boston native and former Bucks County resident was dropping his promising engineering career to orchestrate a cure for the devastating neurological disease. And though it often takes a decade or much longer to achieve any medical breakthrough, he wanted to achieve one in just a year. That's all the time he figured he had, before the effects of the illness - usually fatal in three to five years - became too debilitating for Stephen, a 29-year-old carpenter, to benefit.

Sure, the odds were long, but Weiner couldn't dismiss Heywood's effort. Not at that point in history, right before the turn of the century. Scientists, after all, were cloning sheep. Weiner knew about under-the-radar, genetically engineered human fertility procedures. And there was tremendous excitement over the regenerative potential of stem cells and the rapid progress of the Human Genome Project to map human DNA. In 1999, Weiner knew, the ability to play God, to create and restore life, never seemed more within reach.

"The science looked so promising at the turn of the millennium," Weiner says over espresso at Paganini Ristorante, his favorite Doylestown haunt. "So many of us, both biologists and science writers, got caught up in a kind of superheated utopian fever and felt that enormous changes were possible, in the next minute, for both good and bad. Genomic medicine. Molecular medicine. Regenerative medicine. It also was scary, because we thought the worst possibilities of cloning would be realized overnight, too."

The Heywoods' story, Weiner knew, might ultimately be too sad to write or perhaps to read. But he was struck by Jamie's brave optimism and extraordinary courage in the face of almost certain defeat. And he was amazed at how quickly the charismatic Heywood - not a medical researcher - had put together a team of world-class gene therapy experts, including researchers at Johns Hopkins University and the Jefferson Medical College CNS Gene Therapy Center, and begun raising money to fund the research. Their goal: To pursue a new gene therapy concept in ALS.

Ten years ago, Weiner's career had soared with the publication of The Beak of the Finch,his classic, Pulitzer-Prize winning account of the work of Princeton biologists Rosemary and Peter Grant. Literally eyewitnesses to evolution, which is presumed to proceed at a glacial pace, the Grants were observing year-by-year generational changes in the size and shape of the beaks of Darwin's finches on the Galapagos. Whipsawed between unprecedented drought and record rains, the finches were adapting rapidly to take better advantage of varying seed supplies.

Then Weiner wrote the first book Ralph Greenspan inspired, Time, Love, Memory,which chronicled the efforts of molecular biologists to identify the genetic keys to behavior through DNA work with fruit flies. It won the general nonfiction National Book Critics Circle Award.

The Heywoods' tale, though, had a much more human appeal. It reminded Weiner of ancient Greek myths, like the story of Orpheus searching for his wife, Euridyce, in which the hero attempts to pull a loved one from the underworld.

"It's become very important to me as a writer," Weiner says, "to tell stories that take us everywhere, not just into a lab but into homes, into the adventures of real people in extraordinary moments of everyday life."

Fifty years old, short, with rimless eyeglasses and receding but still dark hair, Weiner's gentle, unpretentious demeanor belies his probing, lucid intellect. He may talk about the Sixers with his 15-year-old son Benjamin. But when he's with his father, Jerome, it's likely to be in the familiar stacks of an Ivy League library. A graduate of Harvard who has taught at Princeton and Rockefeller Universities, Weiner is a self-acknowledged "faculty brat." He was raised in New York and Providence, R.I., where his father was a professor of engineering and applied mathematics, first at Columbia University, then at Brown University.

The Heywoods, too, are faculty offspring: their father, John, is professor of automotive mechanical engineering at MIT in Cambridge, Mass., and their mother, Peggy, is a retired therapist.

That's not all Weiner had in common with the Heywoods. He was doubly moved by their story because his mother, Ponnie, a retired Providence College librarian, was herself suffering from a nerve-death disease, as yet undetermined.

"The emotional ride for the families is incredibly turbulent and painful, no matter how the disease is labeled," he says. "They call it the long good-bye. And in our case, it's been a very long good-bye."

Perhaps, Weiner thought, in writing His Brother's Keeperhe might uncover information that could help his own mother. His Brother's Keeperbecame his most personal book the moment he revealed Ponnie's condition to Matt During, the Heywoods' gene therapy researcher at Jefferson.

As a father of two, and one-half of a writing couple - Weiner's wife, Deborah Heiligman, writes children's books - he understands professional and financial risk. But his admission to During laid bare a vulnerability of an entirely different order.

"What a world of difference there is between asking questions as a professional and professing a desperate need," he writes in His Brother's Keeper."You stop being a doctor or an engineer, an entrepreneur, or a reporter. Suddenly you are just a human being who is very frightened and trying not to beg."

In response, During offered Weiner the possibility of using an experimental neurovaccine he was studying. The offer struck Weiner and his father with both hope and fear. Ultimately, they rejected it.

"It was clearly very, very much on the edge, and there was so little chance it was going to help her," he said. "If I was convinced it was worth doing, I might have been able to convince my father, because he was desperate to help her, but it was already too late."

They made the right decision. Though promising, brain vaccines - in part because of significant side effects - have had a difficult route to federal approval. The Weiners were also unwilling to subject Ponnie to the brain biopsies necessary to diagnose her condition before any vaccine could be administered.

(Subsequently, she was diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy, or PSP. Today, she sleeps much of the time, and is so drowsy when awake that Weiner is not certain she recognizes him any more.)

Nonetheless, experiencing "the shocking transition from a reporter asking questions to a supplicant - 'Can you save my mother?' " - made Weiner realize the extraordinary responsibility that Jamie Heywood had assumed. Heywood's full-court pursuit of a cure freed Stephen to focus his time on building a life - courting and marrying his wife, Wendy, having a son, and directing the rebuilding of a carriage house behind Jamie's home in the Boston suburbs.

Although Stephen received an ineffective stem-cell transfusion, one particular potential gene therapy was the main focus of Jamie and Matt During. An initial animal study had been exciting. But then 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger died during a gene therapy trial at the University of Pennsylvania, and his death had a chilling effect on the research. That, and disappointing lab results, led Jamie to pronounce their concept "clinically dead." (Jefferson also has closed its CNS Gene Therapy Center.)

With his ALS unchecked, today Stephen is confined to a motorized chair and a breathing tube; he communicates through a keypad. Yet, when Weiner last saw him, he remarkably had typed out: "I FEEL LIKE A KING."

In just five years, the foundation Jamie created, ALS Therapy Development Foundation, raised $12 million. Supported by golfer Tom Watson and his ALS-stricken caddy, Bruce Edwards, it now runs what Weiner's book calls the world's largest ALS animal drug-screening program. Even so, His Brother's Keeperis a cautionary tale, an antidote for the hubris that once made Jamie Heywood, Weiner and many others think that anything was medically possible.

"Now it looks like, as fast as our understanding is moving, life is more complicated than we thought in 1999 or 2000," Weiner says. "... It's a lot harder to clone human beings than people realized. Maybe it's so hard to do that the technical obstacles will keep it from happening long enough to sort out the ethical issues that scare us.

"If we can't genetically engineer a cure for ALS yet, which is sad and frustrating, at least we also are far away from being able to engineer a 'new and improved' human species as well."

back to top/pr>

Publisher's Weekly

At the heart of this report from the front lines of gene therapy and other regenerative medicine techniques lies a simple, heartbreaking question: "What would you do to save your brother's life?" When Stephen

Heywood, a 29-year-old carpenter, was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as Lou Gehrigıs disease), his older brother, Jamie, launched his own research project to search for a cure. It was the late 1990s, shortly after scientists had cloned a living creature for the first time. So when Jamie told a friend about research demonstrating that the DNA of every ALS victim was missing a protein, his response (Why don't you just put the damn protein back?) seemed wildly optimistic but not entirely impossible - if they could figure out how to do it in time. Weiner (The Beak of the Finch) keeps the actual science to a minimum. The story's power derives from attention to small, human details, like Stephen's first symptoms of losing strength in his fingers. The emotional register is also strong; Weiner spends so much time with the Heywoods that they begin to refer to him as one of the family, and his closeness allows him to effectively contrast their handling of Stephenıs condition to his own family's reaction to his mother's bout with a similar nerve-death disease. Weiner can't give readers a happy ending for Stephen, but he can--and does--offer a powerful account of equal parts ambition and hope.

back to top

Booklist, March 15, 2004, Starred

Not a baseball star like Lou Gehrig. Just an ordinary carpenter afflicted with the same terrible degenerative disease that struck down the acclaimed ballplayer. But in recounting this carpenter's descent into neuromuscular paralysis and his devoted brotherıs heroic fight to stop that descent, Weiner allows his readers to visit the very frontiers of medical science and to contemplate the oldest of human loyalties. Two intertwined transformations propel the narrative: the doomed sufferer's pathetic metamorphosis from robust and versatile handyman into wheelchair-bound paraplegic and the brother's improbable emergence as a relentless explorer of genetic science deploying the redirected skills of a mechanical engineer. The linked chronicles of personal change teach a great deal about the grim progress of an ugly disease and even more about the promising yet still risky therapies now tantalizing often frustrating desperate patients and hopeful experimenters. His sympathy for both brothers deepened by his own

Mother's downward spiral into nerve-death, Weiner delivers a denouement at once unsentimentally candid and humanely affirmative. A poignant and probing look at both the potential and the limitations of pioneering medicine.

back to top

Austin American-Statesman (Texas), March 28, 2004

By Patrick Beach

Bond of brothers: 'Keeper' is compelling

Whenever a family member is diagnosed with one of those horrible diseases that only happen to other people, the rest of the brood rushes to dampen hysteria and fear with information.

So it is with the Heywoods of New England. It's late 1998. Twenty-nine-year-old Stephen Heywood is diagnosed with ALS, better known as Lou Gehrig's disease -- fatal, incurable, hideous. His sister-in-law, Melinda, reaches for "Tuesdays With Morrie," Mitch Albom's best seller about visits with his former professor who's dying of the same disease. "ALS is like a lit candle: It melts your nerves and leaves your body a pile of wax," Albom writes.

But Heywood's brother, Jamie, says he doesn't need to read it: "I'm not going to read that book," he pronounces. "I'm going to find a cure."

And just like that, Jamie turns himself into a genetic engineer, reading the abstracts of papers, establishing a foundation, putting together a team of researchers who can crash a gene therapy procedure into existence -- all the while jumping through political and regulatory hoops -- before Stephen loses his ability to walk, then speak, then breathe.

"How much of life can we engineer?" Jonathan Weiner writes in "His Brother's Keeper." "How much is permitted us? What would you do to save your brother's life?"

This is a potentially great story with tremendous built-in urgency. And Weiner is a highly decorated science journalist, having won the Pulitzer, the National Book Critics Circle Award and many other honors. Yet the task he assigns himself here seems almost as doomed as Jamie's. Weiner must grasp the science well enough that he can explain it to, but not drown, the lay reader. And he must not lose the human thread -- these are compelling characters in a desperate struggle, after all -- nor can he succumb to the tendency to wallow in misery, even though the story is inherently miserable.

Plainly put, Weiner pulls it off beautifully. "His Brother's Keeper" manages a consistency of tone that's based in solid reporting and bottomless humanity. Weiner, who first wrote about this story for The New Yorker, gets enviable access, which gives the book a revealing intimacy. Yet even as Weiner frets that he may be losing his reportorial impartiality he hangs onto his acuity. This holds true even after the story becomes brutally personal to the author, when his mother is diagnosed with her own neurodegenerative disease -- one that might also benefit from the breakthroughs Jamie chases.

This is something of a departure for Weiner, who has spent his career writing about birds on Galapagos and the like. But he's always had a knack for characterization, and there's no shortage of characters here. Jamie is a hyperfocused polymath who knows his team can fashion a cure in time, and chases the dream to the neglect of the rest of his life. In this respect, he's a bit like another Massachusetts protagonist, Jan Schlichtmann in Jonathan Harr's "A Civil Action." He's both heroic and half-full of hot air; Weiner compares him to The Talented Mr. Ripley and Harold Hill from "The Music Man," con artists both. One suspects if Stephen had been stranded on the moon, Jamie would have built a rocket.

Even late in the book, looking back at a string of disappointments, Jamie's still buzzing. "A mixture of truth, fantasy, real promise and total hype still intertwined throughout his conversations," Weiner writes. "It was fascinating to experience and infinitely renewable, and it was part of Jamie's core." Keep in mind this was in the middle of the tech boom, when entrepreneurs were encouraged to be bold, to dream of new paradigms, whatever that meant.

Stephen, on the other hand, is a cheerful, articulate slacker who accepts his illness with a fatalist's wit even as he marvels at his brother's attempts to thwart it. He and Jamie complement each other, their bond partly the product of competition. Arm wrestling was a favorite activity, and both date the onset of Stephen's symptoms to the time Jamie beat Stephen, a rare if not unprecedented event.

On the theoretical plane, Weiner surveys "the edge of medicine," a place where now-fatal diseases can be fixed up with a trip to the drugstore, where we grow new organs, stop aging, clone ourselves and even design a new, genetically distinct strain of human. Modern medicine's tradition of developing new protocols and treatments through painstaking clinical trials, reviews and regulations has been left in the dust of the leapfrogging progress of genetic research.

But in the end, "His Brother's Keeper" is less about pie in the sky, more about the nexus of that research and what it can and can't do for a pair of brothers. Right now.

back to top

Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), March 14, 2004

Karen Sandstrom, Plain Dealer Book Editor

Search for cure to ALS becomes inspiring tale

In 1998, a young carpenter who was rehabilitating a Victorian home in Palo Alto, Calif., stopped to examine his right hand. The hand had been weakening for a while, but he assumed he had simply overextended himself working on the house.

Now, having just smacked the hand on a mailbox, Stephen Heywood gave it a quick look. He looked again. In a holy-cow moment, Heywood noticed that the shape of his hand had changed.

As journalist Jonathan Weiner writes in his new book, "Stephen held up his left hand with the fingers together, the thumb pressed up against the pointer. In a normal human hand, the muscle makes a bulge, a small, fleshy, wrinkled bulge, right in the crook at the base of the thumb. This bulge is known to anatomists as the thenar eminence. Stephen did not know what it was called, but standing there on the sidewalk he could see that his right hand had lost it. His right hand looked as if the crook between the thumb and the palm had been carved away with a jigsaw."

This discovery sent Heywood to the neurologists who would eventually deliver what might be the worst news a person can hear inside a doctor's office. Still in his 20s, Stephen Heywood had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. ALS causes a gradual loss of motor control, leading to muscular atrophy and eventual death by suffocation. It usually kills its victims between two and five years after diagnosis. "Compared with ALS," Weiner writes, "even brain cancer is a lesser condition."

In "His Brother's Keeper," Weiner presents the story of how Stephen's older brother, Jamie, transformed himself from an MIT-trained engineer into a medical entrepreneur whose ad hoc committee of scientists and researchers worked with the hope of curing Stephen through gene therapy. It is by turns a wrenching, inspiring and mystifying tale done justice by science writer Weiner, who won a Pulitzer Prize for "The Beak of the Finch."

Nonfiction books written by journalists often read like newspaper articles run amok. Trained to write what they know and then prove how they know it, reporters have a way of starching up the silky threads of a story.

Weiner writes like a writer, not like a reporter. If it seems a touch forced that he begins one chapter with a reference to Franz Kafka's short story, "The Imperial Message," the reader soon will concede that a) Weiner makes good use of the prop and b) it's reassuring to be in the hands of a reporter who reads literature. The author maintains a grasp not only on his facts, factoids and metaphors but also on the big picture - the broad beams of meaning on which all else hangs.

"His Brother's Keeper" is really three stories. The first explains the technologies of modern genetics and their implications for the future of humanity. Set in the late 1990s, around the time of the birth of Dolly, the first cloned lamb, the book captures the fear and excitement that surrounded the new scientific knowledge.

"By the last decade of the twentieth century, the power of human understanding had reached a point at which it was possible to view all of life as a project in molecular engineering, and the saving of life as nothing more than engineering and genetic carpentry," Weiner writes. "Now surgeons dreamed of operating on molecules inside the bodies of their patients - hammering, sawing, and polishing. . . . The molecular surgeons had a new and exalted maxim. To teach the body to heal itself molecule by molecule would be to heal like God."

Such God-playing is exactly what Jamie Heywood hopes to do for Stephen. First, Jamie dives into ALS research to understand what doctors know about it. One factor seems to be the overproduction of the neurotransmitter glutamate, which can lead to the death of nerves in the spine, which cuts communication between the brain and muscles.

After speaking with a neuroscientist named Jeffrey Rothstein, who specializes in ALS, Jamie concluded that the goal was to somehow fix the messaging system in his brother's dying spinal nerves. Weiner follows as Jamie tries this, fearlessly presenting scientific information that at times can be hard for a lay reader to follow.

Jamie surrounds himself with experts and information on genetic engineering, gene therapy and stem cells, and builds a think tank. Although Jamie is not a scientist, he throws himself with cowboy zeal into his race against time. The odds of success seem almost too small to consider. Jamie's determination to defy them gives the story its suspense.

The second story Weiner tells is about the singular determination and sense of purpose that the Heywood brothers, their wives and their parents bring to the fight. Raised in suburban Boston, the Heywood boys are smart, accomplished and cocky. As presented by Weiner, they identify themselves in terms of tribe, as in "we are Heywoods." Not every reader will find this aspect of the family appealing.

Still, it's impossible not to admire how they (and especially Jamie) translate pride into maverick action. In a book that charts levels of success and failure, the decision to act is presented as its own kind of success.

The third story concerns the author's relationship to his work as his own mother succumbs to a rare and devastating neurological disorder. Whether Weiner included this out of concern for full disclosure (he had more than a passing interest in genetic treatment) or because the parallel seemed too striking to ignore, the poignancy of his mother's illness deepens an already potent story.

"His Brother's Keeper" fulfills the potential of every great science story. It delves into the perfect mysteries of planet Earth while giving voice to how our species struggles with imperfection. It lifts high the data, then celebrates it with writing that lists toward poetry. It is only appropriate that Weiner's rendering leaves his reader both sadder and more hopeful.

back to top

Entertainment Weekly, April 2, 2004

By Allyssa Lee

His Brother's Keeper

Pulitzer winner Weiner (The Beak of the Finch) follows the Heywoods, a charismatic Massachusetts family rocked by middle son Stephen's diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a.k.a. Lou Gehrig's disease. As 29-year-old Stephen battles its incurable, degenerative neural effects, older brother Jamie suddenly switches careers, from mechanical to genetic engineer, in a medical race to save his sibling. Weiner, whose own mother suffers from a similar ailment, writes an eloquent and engrossing story that's equal parts heartbreaking and hopeful--a very human tale of superhuman will in a molecular world. The Heywoods not only explore the untested boundaries of gene therapy but also maintain faith when "the odds against Jamie's plan were so long that...hope almost felt like the heavier weight."

back to top

The Kansas City Star, March 21, 2004

By Steve Paul

Bio research braided with family's struggle in Keeper;

Book explores frontiers of science, where ethical quandaries reside

Stephen Heywood was reconstructing a house in San Francisco when he began to notice his right hand wasn't working right. That was the first sign of ALS, a dark omen that nerves in his body were dying.

Stephen's brother, Jamie, took it hard. Trained as a mechanical engineer, Jamie had migrated to the raging world of biotech, and it occurred to him that he was in the right place to pursue a cure for the devastating disease. With the right researchers involved, maybe a full-bore effort would yield promising results or at least an experimental treatment that could stop or slow his brother's physical decay.

The chase was on.

That's the spine of His Brother's Keeper, Jonathan Weiner's compelling new look at a family engulfed by an illness and the parallel world -- brave, new and often controversial -- of medical research.

Weiner is the author of The Beak of the Finch, an award-winning science narrative about evolution and Darwinism. More than once in telling his tale of the Heywoods, Weiner wishes to escape back to the paradise that was the Galapagos Islands. To him, the science of the past is so much less wrenching than the science of the future, which, of course, is the science of now.

Jamie Heywood's team of gene researchers seems at times like those guys (and gals) with the right stuff, confident and eager as they soar through the unknown, snipping DNA, reconstructing matter, tinkering under the hood of the human body.

A typical mode of experimental treatment involves hollowing out a virus and inserting a short segment of DNA. Jamie's team put together a DNA package that contained a pertinent gene and another piece of DNA called "woodchuck hepatitis virus post-regulatory element," which had been found to accelerate the effectiveness of the target gene. The whole tiny capsule, millions of them, would be injected into Stephen Heywood's spine.

An earlier test on mice pointed in the right direction, when a single ALS mouse lived months longer than expected, although later it was found to have lost brain capacity.

The risks are enormous, Weiner writes. Yet for some, the tradeoff is worth it.

For Weiner, the Heywoods' story, which he began as an article for The New Yorker, intersects eerily with his own life. His mother is struck by what also appears to be a rare nerve-death disease.

Weiner becomes well-positioned to consider the possibilities of experimental treatment for her as well. But, more important, perhaps, he can thus measure his empathy for the Heywood family against his own feelings prompted by his mother's decline. He spends so much time with the Heywoods -- the men, their wives, their parents in a comfortable Boston suburb -- he becomes an honorary member of the family. For the reader, of course, that means intimate access to otherwise submerged emotional currents.

"To write about medicine," Weiner writes early on, "has always been to confront the whole human experience."

People die. The challenge to the writer who chooses to write about dying is to find the meaning that helps comfort and enlighten those left behind.

Weiner does that in His Brother's Keeper, but by exploring "the edge of medicine," he confronts, too, a dazzling borderland of raw science and hope that doubles as a moral minefield.

Cloning, stem-cell research, gene therapy -- Weiner's book is a compelling, human journey into the social debates over medical ethics and the frontiers of science. How much of life, Weiner asks, are we prepared to engineer?

And how far can a family go to save one of its own?

One of the more important decisions Jamie Heywood faces is whether his lab should be a nonprofit or one that might cash in big on its discoveries.

In the course of Jamie's search for an ALS cure, a gene therapy clinical trial in Philadelphia invites deep scrutiny after the death of an 18-year-old patient. The case grew to scandalous proportions, Weiner notes, and cast a shadow over research projects everywhere in a time of heightened caution and concerted government attention. The regulatory bar got higher, but Jaime Heywood proceeded.

By the end of Weiner's book, Stephen Heywood remains alive. He is debilitated, in a wheelchair, but retains an innate vitality and sense of humor. Weiner comes to some rather surprising yet perhaps inevitable conclusions about the Heywood brothers.

Weiner is a literate companion, and one of his muses is the Roman philosopher Lucretius, a rationalist who penned the phrase, "Life is one long struggle in the dark." Weiner begins his book with a somewhat more optimistic epigraph: "If you would like to know what men really are, the time to learn comes when they stand in danger or in doubt. For then at last words of truth are drawn from the depths of the heart, and the mask is torn off, reality remains."

One morning, as Weiner sits reading in his New York apartment, two planes hit the towers of the World Trade Center, an event that demands perspective as well.

"Biology," he writes, "could be as dangerous as physics, and genetic engineering could make cells worse than bombs. They could kill New York and leave the towers standing. The science of life was as charged with good and evil as the science of the atom had been in the century before."

back to top

Tampa Tribune (Florida), March 21, 2004

By Mark F. Lewis

ALS Victim, Brother Enter Race For Cure

In "Tuesdays With Morrie," Mitch Albom watched helplessly while his college mentor's body slowly succumbed to the ravages of ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). When Stephen Heywood was diagnosed with this illness, his brother Jamie was determined to do better - he would find a cure and find it quickly enough to save Stephen's life.

Pulitzer Prize winner Jonathan Weiner has combined his knowledge of science with insights into family dynamics to produce a touching and almost unbelievable true story. He explains the applicable scientific principles in language readily understandable to the average reader. In Stephen's case, the early symptoms appeared in his right hand, first becoming noticeable when his brother bested him in arm wrestling for the first time in five years. As Weiner explains, "Stephen's motor neurons had begun to die, one by one, and messages were failing to get through to his right hand."

Despite the success of Albom's book and the fact that famed baseball player Lou Gehrig also contracted it, Weiner notes that ALS is still considered an orphan disease. The big pharmaceutical companies don't want to invest literally billions of dollars to find a cure for an illness that affects only 25,000 patients in the United States.

This situation was unacceptable to Jamie, a mechanical engineer. He gave up a position in a California think tank to return home to Massachusetts where he would put his engineering skills to work. In his view, it was really very simple: "If what has broken is nothing but a system made of molecules, an engineer can try to fix it." Working from this basic premise, Jamie recruited a team of scientists to speed up research in the gene therapy that he believed would be the cure.

During this time, Weiner admits that he lost his ability to view this story through the eyes of an objective journalist: "When I let myself hope for Jamie and Stephen, I knew that I got carried away. Illness makes us all yearn for that kind of magic cure." Many times throughout the book, Weiner had to remind himself, and readers, of the almost impossible goal that Jamie had set for himself.

What made it all the more painful for him was knowing that his mother was also losing a battle with a neurodegenerative disease.

In addition to the virtual impossibility of trying to rush a major scientific breakthrough, problems arose in the field of gene therapy that caused the shutting down of much research. Since we haven't read about the discovery of a cure for ALS, you know that the book unfortunately has the predictable ending that you keep hoping would not happen. Even Weiner resigned himself to this fact: "I knew it had to end badly. I think he [Jamie] knew it too. But I still hoped that through sheer energy, will, and intelligence, Jamie would snatch some kind of victory in spite of everything - and not be destroyed with Stephen."

Throughout this work, Weiner also touches on some of the ethical problems endemic in this field: "How much of life can we engineer? Are there any lines we cannot or should not cross?" He stands in awe that "molecular biology was moving so fast that it was capable of experiments as outrageous as anything in the literature of science fiction."

"His Brother's Keeper" can leave you frustrated with the realization that despite the best efforts of the brightest people in the field, there are some things that just cannot be done, at least not on a specific timetable. But it will also give you hope for the future, knowing that there are men such as Jamie Heywood who live by a credo, "If I think there is even a possibility, I can't not do it." It will also leave you with a warm feeling about how one particular family came together during a time of great crisis.

back to top

Library Journal, April 15, 2004, Starred

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Beak of the Finch tells the remarkable story of two close brothers from Massachusetts, brought even closer in 1998 by the younger brother's diagnosis with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease), a degenerative neurological condition. Jamie Heywood, the elder brother, decided to change his career from mechanical engineering to medical research to try to save his brother Stephenıs life. Weiner's descriptions of the ups and downs of stem-cell research, gene therapy, and the ethics of end-of-life experimental treatments grippingly convey the effect of scientific inquiry on regular people. Weiner also meditates on the impact of experimental medicine of the human race as a whole, and his interest in Darwin leads to the idea that genetically modifying human beings to prevent or cure disease may prove to be an evolutionary event that transforms humanity. Touching and insightful about the concepts of family, illness, and the frontiers of medicine, this is strongly recommended for science and medical collections in public and academic libraries.

back to top

Ottawa Citizen, April 18, 2004

James Macgowan

Saving Stephen: When his younger brother was stricken with ALS, Jamie Heywood began a race against time to save his life

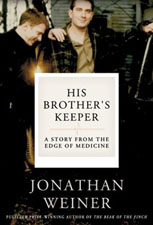

See that picture? That's Stephen Heywood on the right. He's a carpenter, a man who likes building things with his hands. On the left is his brother Jamie. See the protective arm on his brother's shoulder? Just like an older brother, isn't it? He's three years older than Stephen, MIT educated, and an engineer. It's a cheery picture, but looks, as they say, can be deceiving.

The photo is more than four years old and Stephen doesn't look like that anymore. He has ALS and he's dying. He had it when the picture was taken too, it just wasn't as advanced. ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig's disease), is a death sentence, an awful disease that gradually paralyses its victims until they can no longer breathe.

It is the kind of illness that, when it is suspected, and the doctor has finished running his tests, well, it is the kind of illness that makes loved ones hope for brain cancer instead. At least, that's what Jamie and his mother Peggy did as they awaited Stephen's test results in January, 1999.

"With cancer," Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Jonathan Weiner explains in his fascinating and moving new book, His Brother's Keeper: A Story From the Edge of Medicine, "at least there was some chance of a cure. With ALS there was no chance at all."

Stubbornly, Jamie, a driven, charismatic, doggedly determined go getting person if ever there was one, didn't buy into that. "If what has broken is nothing but a system made of molecules," he says at one point, "an engineer can try to fix it."

As soon as Stephen told him that what was changing his right hand into a claw was likely ALS -- this was before an official diagnosis was made -- Jamie turned to his computer and began looking for a cure. He focused quickly on gene therapy and began assembling a team of scientists to speed up research in this area. Given that most people with ALS usually survive no more than five years, Jamie knew this quest would be a race against time.

It is this journey, at times powerfully uplifting, at others heartbreakingly sad and frustrating, that Weiner chronicles, in a story made more personal for him by the fact that his mother was also afflicted with an incurable neurodegenerative disease.

"It was the most intense writing project of my life," Weiner, 50, says, over the phone from his home in Doylestown, Pennsylvania., about an hour north of Philadelphia. "At the same time, it carried me farther emotionally than any of the other books. What I mean by that is, I feel better now, a lot better, for having taken the ride and told the story, and that's why I feel so much more like I've come out the other side."

As he was researching the story, which originally appeared in The New Yorker in February, 2000, he didn't talk much about his personal situation with the Heywoods. And he's careful not to let his pain get in the way of their story, which, because he grew so close to them, was already painful enough.

"I'd never gotten so involved with a subject before and never felt that close," he says. "It really was a family feeling. How could I not feel that way, when my own family just an hour away was going through something similar." He pauses. "I was often knocked over by it. I try to be candid in the book about that to make my own emotional involvement in the story a part of the story because I was swept away. I wasn't much of a reporter after awhile, I was really a participant more than a reporter. It was very hard to hold on to any kind of objectivity."

Weiner is a distinguished science writer, whose books include The Beak of the Finch (which won him the Pulitzer) and Time, Love, Memory. When he talks, he talks with the air of someone who is part of the scientific community. But at one point, he grew frustrated with science, and scientists.

"When it became clear that the gene therapy was not going to save Stephen," he says, "and that we just didn't have anything now for Stephen or for my mother, I felt so sad that, even though I've spent my whole career writing about science and being fascinated by science, it was hard to continue feeling good about science ... If science can't save Stephen and can't save my mother," he says, describing a conversation he had with his wife when all this was going on, "then what good is research?

"It was a natural feeling then," he continues. "I've gotten past that, fortunately. I feel more hopeful and more positive again."

The situation with his mother, who was diagnosed with PSP (progressive supra-nuclear palsy, a disease that has similar symptoms to Alzheimer's) made Weiner realize how much Jamie had taken on. As he found out, it is one thing to watch a loved one's condition deteriorate and quite another to do something about it. Jamie worked a punishing schedule, hardly ever slept and his marriage deteriorated, but it didn't matter. He was going to find a cure.

"Jamie has this incredible can-do, MIT, techy spirit," Weiner says. "He's just convinced he's never met a problem he can't solve."

But this, finding a cure for ALS within a year, was an impossible goal, something Weiner reminds us in the pages of the book. It usually takes 10 years and tens of millions of dollars to develop a drug.

Jamie, of course, had neither. At times, you would be swept away by Jamie's optimism, and then be hit by an expert who would say to Weiner -- and Weiner suspected as much, anyway -- that gene therapy would never save Stephen.

They were right, of course. But it took the death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger in a gene therapy clinical trial to force Jamie to abandon his quest for a gene therapy cure. Instead, Stephen underwent a stem-cell procedure, which had no effect, though it didn't cause him any harm, a not insignificant accomplishment in the world of experimental medicine.

This is the third aspect of Weiner's book, what he calls the edge of medicine, which encompasses the fields of genetic engineering, gene therapy and stem-cell treatments. In February, 1999, when Weiner first heard about Jamie's quest, exciting, apparently miraculous cures were thought to be just around the corner -- indeed, the ability of man to play God was seemingly upon us. That it all came to naught has not discouraged him. He still believes in gene therapy, and says it's crucial in fighting orphan diseases such as ALS.

"The promise is still there," Weiner says. "The research has to be done so that the promise can be fulfilled. It's not going to be tomorrow, but in another 10 years or 20 years, gene therapy will be a phenomenal source for cures for what are now incurable diseases. Same thing with stem cells."

In the final analysis, Jamie's biggest problem was that he was dealing with an "orphan disease." Simply put, these are diseases that don't kill enough people to make them financially attractive to drug companies to seek a cure. In the U.S., it's thought that 25,000 people suffer from ALS; in Canada, that figure is between 1,500 and 2,000. That's too low to turn a profit, so it's up to edgier medical procedures to fill the void.

"My sense," says Weiner, "is that unless we support research at the edge of medicine better than we're doing right now, many more of us will find ourselves dealing with diseases that are virtually orphaned."

It's too late for Stephen, of course. Oddly, though, it is not Stephen who Weiner is worried about as the book ends.

"Everyone close to Jamie was worried about him from the beginning," Weiner says. "Because he's taken on so much that, if he does lose -- and he hasn't given up yet -- if he can't manage to save Stephen, then how will he go forward? Will he be able to go forward? I think everyone worries about that for him."

A couple of weeks ago, Weiner and his wife Debbie were speaking with Jamie on the phone. She had just finished re-reading Jonathan's book and said to him: "What an incredible race it was." Jamie answered: "It still is," a response that suggests he's wearing a powerful set of blinders.

You know, you can look at it that way," Weiner says, "or you can look at it as the power of hope that helps make the impossible happen. I mean, we need people like that. As long as he's not being so unrealistic that he's wasting his time or wasting donors' money." Weiner pauses. "I think we're fortunate that he's in the race."

As for Stephen, he is, at the end of the book, just a shell of what he once was. But he's found peace, the peace that eludes his brother. He has a wife, a three-year-old boy and, astonishingly, a happy and healthy outlook.

"He's a guy who found himself," Weiner explains, "even as he was dying."

back to top

Raleigh News and Observer, May 9, 2004

Phillip Manning

The cure hunter

Stephen Heywood went to the neurology clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital just before Christmas in 1998. He was only 29 years old, but his right arm had weakened and become thinner during the past year. Earlier, a doctor had mentioned the possibility that Stephen had ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Lou Gehrig's disease). Stephen had ignored him. This time, though, the withering of the muscles of his right hand and arm was obvious. "There's some weird stuff here," the neurologist said. The doctor refused to put a name to the "weird stuff," but Stephen knew what he meant: He had ALS. He also knew why the doctor was reluctant to tell him directly. The diagnosis is a death sentence; there is no cure for ALS, and most patients die within two years of diagnosis.

Doctors have been delivering devastating news of this sort to patients for centuries. Afterward, families gather to console the victims who are likely facing long, debilitating illnesses followed by death. Stephen followed this ancient script and contacted his loved ones to tell them the bad news. But technology has changed the way some people react to incurable diseases. When Stephen called his brother Jaime, an engineer in La Jolla, California, Jaime did not offer platitudes. Instead he did something that families couldn't do a few decades ago. He turned to the computer on his desk and punched in

"ALS." He read abstract after abstract. Then he resigned from his job and vowed to "find some way to pull Stephen back from the dead."

In "His Brother's Keeper," the Pulitzer-prize-winning science writer

Jonathan Weiner tells the gripping story of Jaime's race to save his brother from ALS. The story vividly illustrates how science and technology have changed the relationship between patient and physician. Patients and caregivers can access Web sites for almost every disease and get crucial information on experimental drugs and procedures, giving them far more insight about how their illness should be treated.

Jaime's first job was to learn all he could about ALS. He discovered that it is an insidious disease that attacks the motor neurons, the nerve cells that carry messages from brain to muscles. Stephen's motor neurons were dying, the messages sent by his brain to his right arm were not getting through, and his muscles were wasting away. The disease progression is inexorable and well-documented. Stephen would get weaker, and his voice would fail. He

would be confined to a wheelchair and forced to communicate with a voice synthesizer, as Stephen Hawking, the noted theoretical physicist and fellow ALS sufferer, does. Eventually, he might be unable to swallow; he could drown in his own saliva. Why was this happening, wondered Jamie. And what could he -- with his charm, his fast-talking intensity, his entrepreneurial spirit, and his supportive and well-connected family -- do about it?

As he absorbed information about ALS, Jaime came across a paper by Dr.

Jeffrey Rothstein of Johns Hopkins University. Rothstein suggested that the nerve death associated with the disease might be due to unusually low levels of a protein. Jaime jumped at the news. Why not insert the DNA that made the protein into Stephen's dying nerves? Gene therapy, as it is called, was the rage in the late 1990s. Biotech companies promising gene therapy miracles were springing up all over, even though its successes were almost nil. "I'm going to find a cure," Jaime told his wife.

Jaime did not limit himself to investigating gene therapy. In a frenzy of activity, he found a scientist working on a neurological vaccine. Might this work for Stephen, he asked himself. Let's pursue that lead, too. A stem cell injection of the patient's own blood at the base of the brain might make new nerve cells. Could work, thought Jaime. As Jaime worked, Stephen tried to forget his ailment. He wanted to live whatever life he had left to the fullest. He considered buying a Harley and sowing "wild oats for a few years." Instead, he decided to marry his girlfriend.

Meanwhile, Jaime was moving fast. He formed a nonprofit organization devoted to finding a cure for ALS and raised $240,000 to finance it. Weiner, who was shadowing Jaime's every move to write a story about him for The New Yorker magazine, begins to believe Jaime might be able to pull it off. Weiner then becomes part of the story himself. His mother is suffering from a deadly neurological disorder, later identified as supranuclear palsy. Weiner had long ago concluded she was incurable. But Jaime's vaccine might help her. Dare he hope again?

Jaime's frenetic search takes Weiner and the reader on a roller coaster ride from hopeful highs to despondent lows. The ride takes a terrible toll on both men. Weiner dreams of returning to the simple, peaceful life he led while living in a tent in the Galapagos, the setting for his book on evolution, "The Beak of the Finch." Jaime fantasizes about using his newly acquired knowledge of vaccines and gene therapy to cash in on the biotech boom. He and a friend start a small biotech company. Why not save Stephen -- and get rich, too?

One by one, the pipe dreams of both men are dashed. On Sept. 17, 1999, Jesse Gelsinger, one of the first volunteers in a gene-therapy trial, died of complications from the treatment, and the FDA and other sponsoring organizations put a hold on gene-therapy trials. The neurovaccine turns out to be too unproven to try on Stephen, and Weiner's mother's condition deteriorates to the point that he realizes nothing can help her. Finally, the stock market boom that fueled the Internet and biotech bubbles goes bust. Jaime, the entrepreneur who wants to save ALS patients and get rich, realizes that his fledgling business is never going to get off the ground.

In the end, Jaime selects stem cell injections as the best chance for his brother. Stephen undergoes the difficult procedure without harm but realizes no benefit from the treatment. However, despite setbacks and defeats, this is a story about hope, and though I will not reveal the book's ending, it concludes on a heartening note. It is a note that doesn't depend on miracle cures but arises from the resilience of the human spirit.

back to top

New England Journal of Medicine, May 9, 2004

Lewis P. Rowland, M.D.

Jonathan Weiner is a talented science writer. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his book on Darwin's finches and a National Book Critics Circle Award for one on the genetics of behavior in drosophila. Here he tells the poignant story of Stephen Heywood, a carpenter whose right hand became weak in 1997; he was 28 years old. The diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed later; only 5 percent of all people with ALS have symptoms before the age of 30. Also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, ALS is incurable and lethal.

Stephen's brother, Jamie, was working as an assistant to Nobel Prize winner Gerald Edelman at the Neurosciences Institute outside San Diego, California. An engineer trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Jamie Heywood was hired to bring think-tank discoveries to market, and with his commitment to saving his brother's life, he came upon the idea of gene therapy. Weiner heard about the plan from a neuroscientist friend and was himself primed for the project. He had promised to write an article for the New Yorker, and he had a personal interest: his mother had been diagnosed with another nasty neurologic disease, a parkinsonismbehaviordementia disorder, also incurable. Weiner contacted Jamie Heywood and rapidly became part of the project himself.

He was attracted by the pursuit of an idea at "the edge of medicine," a fuzzy line where hope blurs with harsh reality. Jamie created a foundation to develop the idea. He enlisted the aid of two of the most outstanding ALS investigators: Robert Brown at Harvard, who had confirmed the diagnosis, and Jeffrey Rothstein at Johns Hopkins, who had found that the malfunction of a particular gene in ALS could result in the accumulation of glutamate, a natural neurotransmitter; an excessive amount of glutamate could be toxic to motor neurons. Jamie also found Matthew During, a Philadelphia neurosurgeon, who would insert corrective genes directly into Stephen's spinal cord.

Weiner tells the story as though it were powerful fiction by focusing on the personal aspects of the case but not ignoring the social issues. In the end, gene therapy was halted when a teenage volunteer in a trial at the University of Pennsylvania died. So instead of the gene, Stephen's doctors injected stem cells into his cerebrospinal fluid; this was not harmful but gave no benefit.

Some call it "guerrilla science" when families direct research themselves because they are impatient with the bradykinetic pace of conventional research. It can take years to develop an experimental approach, prepare an application for funding, wait until the application is reviewed and revised, and finally get started on the research. Stephen's family did not know how long he would live. In fact, he is still alive in 2004, but at the time it seemed that he might live only a year or two. They were understandably in a hurry.

Rothstein was involved at two levels. His research findings had provided the idea of gene therapy. By the time that approach was scratched, he had become a leader in stem-cell research. Throughout the book, Rothstein is quoted as a voice of caution; animal experiments should precede human application, he warns, to ensure safety and to provide evidence of efficacy.

In the end, Jamie Heywood raised millions of dollars a story in itself. His foundation's Web site now lists six doctoral scientists who focus on "high-throughput drug development" and screen thousands of compounds already approved for other uses by the Food and Drug Administration. The trick is to develop an assay that reliably predicts which drugs could be beneficial in treating ALS.

Among the questions raised in the book are whether the company could raise more research money as a for-profit or a nonprofit entity, whether someone with a deadly disease can give truly informed consent to participate in risky human experiments, whether nonscientists can "pick something to do that the researchers in the field didn't pick," and whether conventional science is too timid in moving from laboratory to sick people.

Can we learn from this experience? Stephen's hope rests on the remarkable progress made in the past decade and now accelerating worldwide. Most funding comes from the National Institutes of Health; private donors choose from organizations like the Muscular Dystrophy Association or the ALS Association, family sponsors like the Heywoods or the Estess family's Project ALS, or medical schools. Supporting fundamental ALS research is laudable in all these approaches.

In the meantime, both of the Heywood brothers have married and had children. Readers will appreciate their fascinating story and will certainly join them in the hope that basic research will pay off. All of us who are engaged in patient care and research in ALS devoutly believe it will, but when?

back to top

Seattle Times, May 9, 2004

D.J. Morel

Pushing boundaries to find a cure

The first sign of trouble for the Heywood family came during an arm-wrestling match. Stephen, the 28-year-old slacker of the Heywood clan, who had a fondness for Harley motorcycles, normally had little trouble defeating his brother Jamie, with his MIT degree and fancy desk job.

Only this time was different. Less than two years later Stephen was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig's disease for the famous baseball player who succumbed to it. By then his right arm was paralyzed. The diagnosis meant that this paralysis would spread through the rest of his body until it ultimately killed him, likely a few years later.

In "His Brother's Keeper," Jonathan Weiner details both the rapid decline of Stephen Heywood and the lengths his brother Jamie undertook to save him. An employee at a scientific-research think tank, the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, Calif., Jamie pored over every published study on ALS. With no official medical training, he formulated a theory for a potential cure. He quit his job, returning to the family home in Massachusetts to establish the ALS Therapy Development Foundation. To date, this organization has raised more than $12 million and pushed the boundaries for several new treatments of ALS and other "orphan" diseases, those which have too few cases to interest the major pharmaceutical companies.

Weiner, author of "Time, Love, Memory" and the Pulitzer Prize-winning "The Beak of the Finch," does a remarkable job of explaining the history of medicine and the snail's pace at which it has progressed over centuries. He also introduces the layman to genetic engineering, both its potentially miraculous therapies and the brave new world it could usher in, including treatments that may so alter a patient's personality that they will not function as true "cures" at all.

In the end, "His Brother's Keeper" is far more about people than science. Weiner also writes of his mother as she succumbs to another neurological disease. His descriptions of their quiet moments together as her demure personality turns sour number among the most disturbingly beautiful passages in the book, a clear testament to the need for the type of hope that Jamie Heywood offers in abundance.

back to top

The Washington Post, May 23, 2004

By Susan Okie

Miracle Hunder